Pencil-beam scanning catheter for intracoronary optical coherence tomography

1 Introduction

Intracoronary optical coherence tomography (ICOCT) is a specific application of optical coherence tomography (OCT) technology1-6. Benefiting from its high axial resolution (~10 µm), large imaging depth (>2 mm), and video-rate imaging speed, ICOCT becomes more and more popular in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) surgery7-10. Similar to the function of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), ICOCT is normally applied to assess the intravascular plaque portrait before stent implantation and to evaluate stent attachment after the surgery.

Since most of the lesions locate deeply inside human body and typically happen at small blood vessel with diameter of ~2 mm (human coronary arteries for an instance), ICOCT has unique system structures. The major difference between ICOCT with other OCT implementations is the light scanning device. Different from ophthalmology OCT where galvanometer or MEMS scanning mirrors are generally used, a type of meters long soft imaging catheter is a standard configuration for ICOCT11-14. The probe inside imaging catheter is rotated and pulled back to get three-dimensional (3D) images of an artery lumen. Currently, most of the ICOCT imaging catheters are side-viewing, and there are two subcategories, i.e. distal-driven and proximal-driven catheters. Distal-driven catheter relies on a ~1-mm diameter micro-motor with several thousand revolutions per second (rps) rotation speed, while proximal-driven catheter uses much smaller driveshaft with diameter of about 0.5 mm to transmit torque from proximal end to distal end13-18. Since the optical probes in proximal-driven catheters are normally all-fiber based and they are easy to manufacture at low cost compared with micro-motors, disposable proximal-end driven catheters are the workhorses in current PCI surgery.

Optical probe is the key component in proximal-driven catheter. The probe consists of meters of single-mode fiber (SMF) to guide near infrared light at 1310-nm band in general and a distal focusing optics to focus the light beam onto lesions as well as to collect back-reflected photons. Working distance, depth of focus, and spot size are three vital parameters to evaluate the performance of probes. Some novel micro lenses and designs are developed to extend working distance, enlarge depth of focus, and minimize spot size19-27. Although new technologies develop rapidly, most current ICOCT catheters implement ball lens or gradient index (GRIN) lens. Ball lens catheter has simple architecture and it avoids chromatic aberration intrinsically which makes it quite promising at shorter working wavelength like 800-nm band20. Different from ball lens scheme, GRIN lens design adopts GRIN fiber to focus light beam.

In current mainstream GRIN lens probe, a glass rod spacer is set before a GRIN lens to expand light beam for desired beam profile28-34. This design provides great flexibility to control beam profile. However, it has several shortcomings. Firstly, the length of the glass rod spacer with several hundred micrometers is crucial and should be well controlled which is difficult to manipulate in practice. Secondly, since the light beam is expanded before GRIN lens, it is hard to fabricate small size catheters by a small GRIN lens. A large size GRIN lens is hard to be fusion spliced directly with conventional SMF and UV curing might be applied. UV curing needs well alignment and back-reflection might be strong. Thirdly, conventional probe always has a large gradient constant (large-g, g>2 mm–1) GRIN lens to provide a stronger focus ability. Stronger focus ability can focus the light beam in a small spot but will diverge the light beam quickly with a short depth of focus. The quickly diverged light beam lower the lateral resolution especially for deep tissue. Finally, a focused light beam brings high back reflection power easily when the probe scans the metal stent surface. High back-reflection power saturates the photodetector and generates artifacts in images. Indeed, the focused light beam can be replaced by a narrow nearly collimated light beam which is generally referred to as pencil beam35, and the spacer plus large-g GRIN lens combination can be optimized by the scheme of only using a low gradient constant (low-g) GRIN lens. Reed et al. reported the application of this scheme where a variety of GRIN lenses with g varying from 2 to 4 mm–1 were fabricated to make probes and a probe was successfully used to measure rats brain motion29.

In this paper, we further prove the effectiveness of this spacer-removed scheme and extend its application to intracoronary imaging applications. In detail, a type of all-fiber probe for proximal-driven ICOCT catheter is demonstrated with a g=1.8 mm–1 GRIN lens which was spliced directly with the SMF and no glass rod spacer was incorporated. The GRIN lens has 1/4 pitch and the output beam is pencil beam, i.e. no focus point. The pencil beam has 0.8 degree full divergence angle, and the full width at half maximum (FWHM) beam size varies from 35.1 µm to 75.3 µm in air over 3-mm imaging range. Probe design principles and probe/catheter fabrication as well as test results are elaborated in Probe design and realization and Catheter fabrication and performance test, respectively. The in vivo imaging capability of the catheter is verified by a clinical ICOCT system with a stent-implanted beating porcine heart as the sample as demonstrated in In vivo porcine intracoronary imaging.

2 Probe design and realization

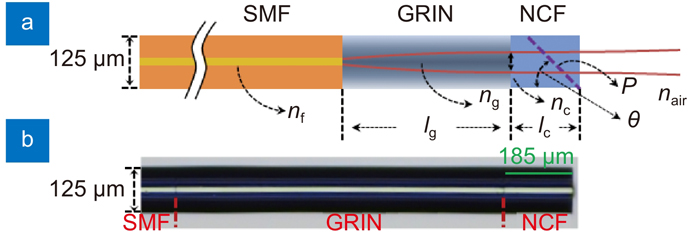

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of the spacer-removed probe. nf, ng, nc, and nair are the refractive index of SMF core, GRIN fiber at the center, NCF, and air, respectively; lg and lc are the length of GRIN fiber and NCF; P and θ are the polishing surface and tilt angle.

The output beam parameters after the NCF can be quantified by ABCD metrics. The working distance (Zw) and beam waist (ws) of the output beam can be calculated by31

where w0 is the beam radius of the SMF; a0=λ/(πw02) and λ is working wavelength; g is the gradient constant of the GRIN lens.

Since the output beam can be treated as Gaussian beam, the Rayleigh length (zR) is determined by zR= πws2/λ in air. According to Gaussian beam transmission law, the beam radius at z position away from the beam waist is determined by w(z)=ws(1+(z/zR)2)1/2. Therefore, the beam divergence angle at position z can be calculated by θ=2arctan(FWHM((w(z)-ws))/z) in radians.

A type of customized GRIN fiber was used to fabricate this low-NA spacer-removed probe. The refractive-index profile (RIP) of this GRIN fiber was measured by a refractive index profiler (S14, Photon Kinetics, Inc) as shown in

Fig. 2. (a ) Refractive index of the GRIN fiber. Inset: cross section of GRIN fiber captured by the refractive index profiler. (b ) FWHM beam size at different position. Inset: beam profile at 2-mm position (left top); beam measurement setup (right bottom).

By taking the values of refractive index ng and gradient constant g into

Fig. 3. (a ) Working distance and Rayleigh length versus different GRIN fiber length. (b ) Beam size and divergence angle versus different GRIN fiber length.

Since 3-mm is long enough for ICOCT application and a smaller divergence angle is important to achieve balanced lateral resolution within the whole imaging range, 1/4 pitch GRIN fiber was used to fabricate the probe which is shown in

3 Catheter fabrication and performance test

The probe was polished 40-degree angle at the NCF to deflect the light beam for side-viewing. The polished probe is shown in

Fig. 4. (a ) Angle-polished probe. (b ) Distal optics with coil. (c ) Distal image of assembled catheter with a guide wire and radiopaque marker. (d ) Full view of the whole catheter. (e ) Connection of the catheter and PIU. Inset: cap used to house the SC/APC connector. U: UV adhesive; C: double-wrapped torque coil; P: plastic sheath; M: radiopaque marker; G: 0.014-inch guide wire; T: catheter; L: Luer connector.

The full view of the catheter is shown in

The optical insertion loss of the catheter is 0.8 dB. The beam size at different imaging depth was measured by the same beam analyzer (BP209-IR/M, Thorlabs, USA) in air with a tilt angle to ensure perpendicular incidence of the light beam from the angle-polished probe. During the measurement, the outer surface of the plastic sheath coincided with the sample surface of the beam analyzer, and thus the beam size measuring started at 0.93-mm from the outer surface of the sheath. The catheter was moved by the translation stage with 0.5-mm step size. To prove the large imaging range of the catheter, beam size evolution over 3-mm range were quantified, i.e. 0.93-mm to 3.93 mm starting from the outer surface of the sheath and it is 1.36 mm to 4.36 mm starting from the center of NCF considering 0.43-mm radius of the catheter. The measured FWHM beam size versus distance is shown in

Fig. 5. Catheter FWHM beam size at different imaging depth. X: horizontal direction, Y: vertical direction. Inset: beam profile at 2-mm position (right bottom); beam size measurement setup (left top).

4 In vivo porcine intracoronary imaging

A healthy 4-month-old domestic porcine was anesthetized first for the in vivo intracoronary imaging as shown in

Fig. 6. (a ) in vivo imaging arrangement. (b ) X-ray image of porcine heart in this experiment. (c ) Cross-section image without stent attachment. (d ) Cross-section image with the stent. (e ) Cutaway view of the 3D image of a segment of coronary artery with stent and guide wire. ECG: electrocardiogram; G: guidewire; H: healthy blood vessel wall; T: catheter; L: small blood vessel branch; S: stent.

The in vivo porcine intracoronary imaging was conducted with the second-generation clinical P60TM imaging system (Vivolight Medical Device & Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). The system works at 1310 nm optical wavelength regime with 11-µm axial resolution in air (7.9-µm in tissue). The A-scan rate of the system is 100 kHz (1024 samples per A-line) and 2048 A-lines per one B-scan. The output power after the catheter was about 10 mW and the imaging sensitivity of the system is 102 dB. The PIU can drive the catheter at maximum 200 rps rotation speed and pull back the catheter of a maximum 60-mm distance within 3 seconds for blood vessel lumen imaging.

In this proof of concept experiment, imaging data were recorded directly from the clinical ICOCT system without post processing. During imaging, the blood vessel lumen was flushed and fulfilled with contrast agent to remove blood to diminish scattering. The intracoronary images captured by this spacer-removed no-focus catheter are shown in

5 Conclusions

In summary, a type of novel spacer-removed probe for ICOCT catheter is demonstrated, and a full-featured ICOCT catheter was assembled based on this probe. The output beam of the catheter is pencil beam, i.e. no focus spot. The imaging capability of the catheter was tested in a clinical ICOCT system with a stent-implanted beating porcine heart as the sample. The FWHM beam size of the catheter ranges from 35.1 µm to 75.3 µm over 3 mm imaging range. Although the beam size of this catheter is slightly larger than conventional catheters, it has much larger depth of focus with small divergence angle, which makes it has uniform beam profile within the whole imaging range. Moreover, since there is no focus spot, the back-reflection power from strong reflective surfaces, say metal stent surfaces, is minimized which diminishes the possibility of photodetector saturation and avoids artifacts in images consequently. In addition, the fabrication process can be simplified since the spacer is removed which benefits mass production in practice.

[1] Drexler W, Fujimoto JG. Optical Coherence Tomography: Technology and Application (Springer, Germany, 2008).

[6] Yun SH, Tearney GJ, Vakoc BJ, Shishkov M, Oh WY et alComprehensive volumetric optical microscopy in vivoNat Med20061214291433

[10] Regar E, van Leeuwen AMGJ, Serruys PW. Optical Coherence Tomography in Cardiovascular Research (Informa Healthcare, London, 2007).

[11] Schuman JS, Puliafito CA, Fujimoto JG, Duker JS. Optical Coherence Tomography of Ocular Diseases 3rd ed (Slack Incorporated, Thorofare, 2012).

[18] Swanson E, Petersen CL, McNamara E, Lamport RB, Kelly DL. Ultra-small optical probes, imaging optics, and methods for using same. United States Patent: 6445939, September 3, 2002.

[28] Tearney GJ. Optical biopsy of in vivo tissue using optical coherence tomography (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, 1997).

[35] Wang LV, Wu HI. Biomedical Optics: Principles and Imaging (Wiley-Interscience, Hoboken, 2007).

Article Outline

Jiqiang Kang, Rui Zhu, Yunxu Sun, Jianan Li, Kenneth K. Y. Wong. Pencil-beam scanning catheter for intracoronary optical coherence tomography[J]. Opto-Electronic Advances, 2022, 5(3): 200050.